Table of Contents

Parkinson’s Disease: Is the Gut the Missing Piece of the Puzzle?

Did you know that gastrointestinal symptoms often appear years before tremors and other key features of Parkinson’s disease? That’s why scientists now think the gut may be where the disease actually begins.

As our gut and brain are closely connected through the gut-brain axis, it’s becoming clear that changes in our gut microbiome could have a much bigger impact on our brain health than previously thought. So, let’s consider how this connection might help to explain the onset and progression of Parkinson’s disease.

Understanding Parkinson’s Disease and How It Affects the Brain and Body

Parkinson’s disease is a progressive neurodegenerative condition that primarily affects the brain’s control over movement. It leads to hallmark motor symptoms such as tremors, rigidity or stiffness, slow movements, unstable posture and a characteristic shuffling gait with reduced arm swing. In addition, patients may also experience non-motor symptoms, such as fatigue, sleep disturbances, gut issues and changes in mood and cognition.

The underlying cause of these symptoms is the progressive loss of nerve cells within the substantia nigra, a part of the brain responsible for producing dopamine, which helps to control movement. By the time motor symptoms lead to a diagnosis, it is estimated that 60-80% of these vital cells may already be lost (1). Alongside dopamine depletion, individuals with Parkinson’s often experience a reduction in norepinephrine, a neurotransmitter involved in regulating automatic bodily functions such as blood pressure. They also commonly develop Lewy bodies, which are abnormal protein clumps that accumulate inside brain cells.

Parkinson’s disease usually develops in people over the age of 50, and it is slightly more common in men than women. While we don’t really know what causes the loss of these nerve cells, experts believe it to be a combination of genetics, environment and our lifestyle. Given that gastrointestinal problems, such as constipation, are frequently reported in people with Parkinson’s disease, research has begun to focus on the gut. Increasingly, evidence suggests that changes there may play a role in how Parkinson’s develops and progresses.

Parkinson’s Disease and the Gut Microbiome

Parkinson’s Disease and the Gut Microbiome

Scientists have discovered noticeable changes in the gut microbiome of people living with Parkinson’s disease. Certain types of bacteria are found in higher amounts, while others that usually support gut health seem to be reduced. These imbalances may not only affect digestion but could also influence inflammation and nerve function, potentially playing a role in how the disease develops and progresses.

A 2023 study took a closer look at this link, analyzing gut bacteria samples from people with Parkinson’s and those without (2) The researchers discovered that close to 30% of the gut bacteria population was altered in people living with Parkinson’s, with increases in bacteria such as Bifidobacterium dentium, and lower levels of helpful species, including Roseburia intestinalis.

Likewise, current research, brought together in a recent review, also highlights consistent findings of gut dysbiosis in people with Parkinson’s disease (3) For instance, it reports a decrease in beneficial, short-chain fatty acid (SCFA)-producing bacteria such as Faecalibacterium, Prevotella, Lachnospiraceae, Blautia, Coprococcus and Roseburia and an increase in potentially pro-inflammatory or opportunistic bacteria, including Escherichia, Shigella and Klebsiella. Other bacteria found to be increased in people with Parkinson’s disease include Akkermansia, Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Porphyromonas, Corynebacterium and Desulfovibrio.

The authors of this review also noted that people with Parkinson’s disease had significantly lower SCFA production (particularly butyrate), alterations in tryptophan metabolism and higher levels of fecal calprotectin, a marker of intestinal inflammation. Importantly, microbial imbalances were observed even in patients with early-stage disease who had not yet received treatment, suggesting these changes are not simply a consequence of disease progression.

Together, these findings suggest that the gut microbiome in Parkinson’s disease consistently displays features indicative of a pro-inflammatory state. This gut-driven chronic inflammation is increasingly believed to play a key role in linking microbial dysbiosis with the systemic inflammation and neuroinflammation seen in Parkinson’s disease.

Is Improving Gut Health a Promising Strategy for Managing Parkinson’s?

With evidence confirming the gut’s role in both inflammation and brain function, this raises the question of whether we can modulate the microbiome to improve symptoms and perhaps alter the course of Parkinson’s disease.

Research has already revealed that deliberately shifting the gut microbiome can positively impact people with Parkinson’s disease. For example, a study published in 2024 found that when Parkinson’s disease patients adhered to a healthier diet (characterized by a higher Healthy Eating Index score and increased fiber intake), their gut microbiome had a greater abundance of potentially anti-inflammatory bacteria, such as the butyrate-producing Butyricicoccus and Coprococcus. (4) While those consuming a higher intake of added sugar had an increase in potentially pro-inflammatory bacteria, including Klebsiella. Furthermore, the study’s analysis of predicted bacterial functions suggested that healthier diets were linked to a decrease in genes involved in producing inflammatory molecules such as lipopolysaccharide, while a decrease in genes related to taurine degradation indicated potentially reduced neuroinflammation.

Another promising area of research focuses specifically on the butyrate-stimulating capacity of various dietary fibers and fiber-rich vegetables. Research has shown that specific dietary fibers, such as inulin and β-glucans, can boost butyrate levels, helping to support health (5) While overall butyrate production remained lower in Parkinson’s disease patients compared to healthy individuals, these findings suggest that targeted dietary interventions could help to adapt the microbiome and support disease management.

In this regard, microbial-directed therapies, such as probiotics, are also emerging as potential therapeutic options for Parkinson’s disease. Indeed, research using animal models suggests they could have protective effects on the brain’s dopamine-producing cells (6) Meanwhile, in human patients, evidence suggests that probiotics may be an effective treatment for constipation, a common non-motor symptom of Parkinson’s disease. However, more research is needed to determine the effects of probiotics on other Parkinson’s symptoms.

Overall, these findings strongly suggest that making changes aimed at rebalancing the gut microbiome is a promising strategy for managing Parkinson’s disease. Modulating the gut could offer new ways to help improve symptoms and potentially influence the disease’s progression.

Using Microbiome Analysis to Guide Gut Health Changes in Parkinson’s Disease

Using Microbiome Analysis to Guide Gut Health Changes in Parkinson’s Disease

With so much information out there, it can be overwhelming to determine which nutritional and lifestyle changes are best suited to your unique needs. This is where gut microbiome analysis can make all the difference.

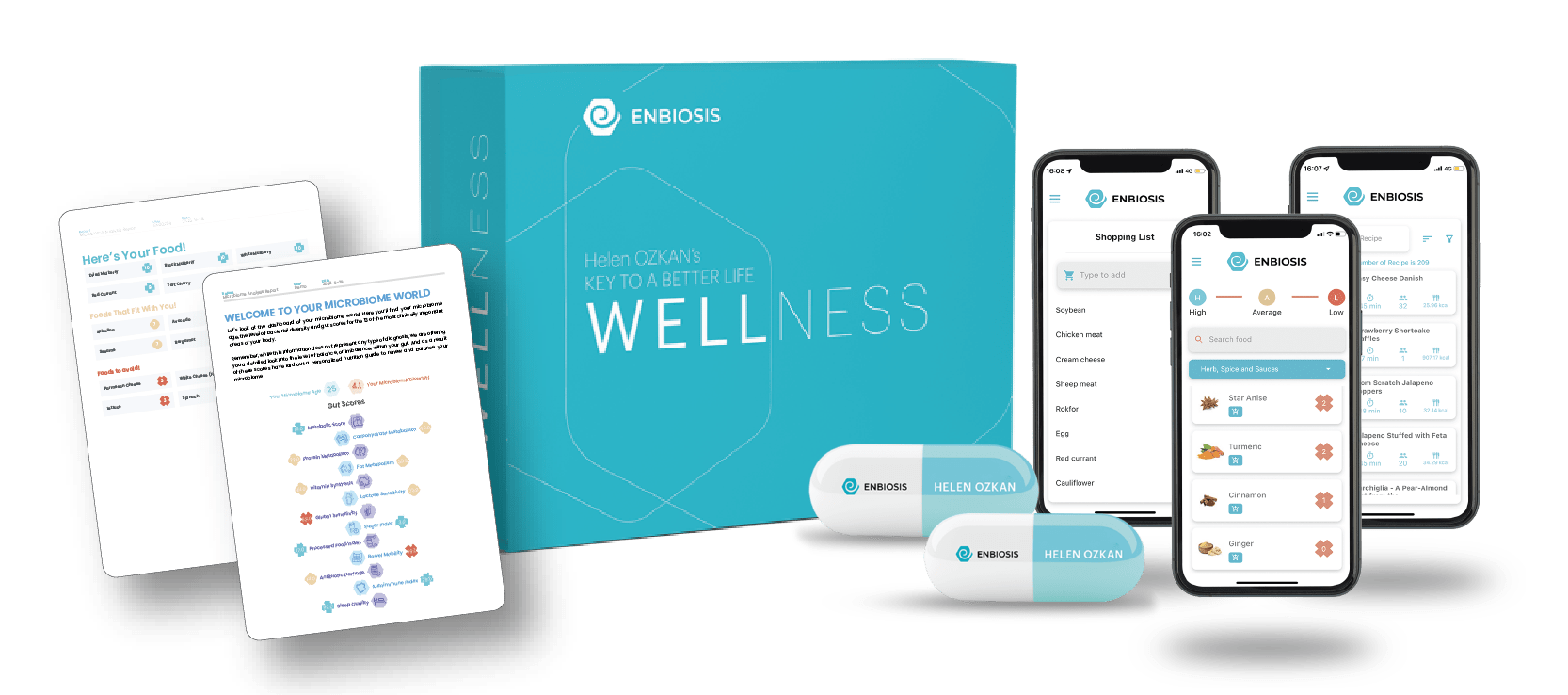

At Enbiosis, our AI-powered microbiome analysis provides personalized insights into your gut health, helping you to make informed decisions about the dietary and probiotic interventions that could benefit you most.

Discover how a personalized gut health strategy, guided by Enbiosis’s advanced AI-powered microbiome analysis, could make a difference for you. Visit our website or contact us today to learn more about our innovative microbiome testing services.

Contact Us

References:

1.National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (n.d.). Parkinson’s disease: Challenges, progress, and promise. National Institutes of Health. Retrieved April 30, 2025, from https://www.ninds.nih.gov/current-research/focus-disorders/parkinsons-disease-research/parkinsons-disease-challenges-progress-and-promise

2.Wallen, Z. D., Demirkan, A., Twa, G., Cohen, G., Dean, M. N., Standaert, D. G., Sampson, T. R., & Payami, H. (2022). Metagenomics of Parkinson’s disease implicates the gut microbiome in multiple disease mechanisms. Nature Communications, 13(1), 1-20.

3.Suresh, S. B., Malireddi, A., Abera, M., Noor, K., Ansar, M., Boddeti, S., & Nath, T. S. (2024). Gut Microbiome and Its Role in Parkinson’s Disease. Cureus, 16(11), e73150.

4 Kwon, D., Zhang, K., Paul, K. C., Folle, A. D., Del Rosario, I., Jacobs, J. P., Keener, A. M., Bronstein, J. M., & Ritz, B. (2024). Diet and the gut microbiome in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Npj Parkinson’s Disease, 10(1), 1-9.

5 Baert, F., Matthys, C., Maselyne, J., Poucke, C. V., Coillie, E. V., Bergmans, B., & Vlaemynck, G. (2021). Parkinson’s disease patients’ short chain fatty acids production capacity after in vitro fecal fiber fermentation. NPJ Parkinson’s Disease, 7, 72.

6 Tan, A. H., Hor, J. W., Chong, C. W., & Lim, Y. (2020). Probiotics for Parkinson’s disease: Current evidence and future directions. JGH Open: An Open Access Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 5(4), 414.